A Novel Inspired by Irena Sendler, Heroine of the Warsaw Ghetto

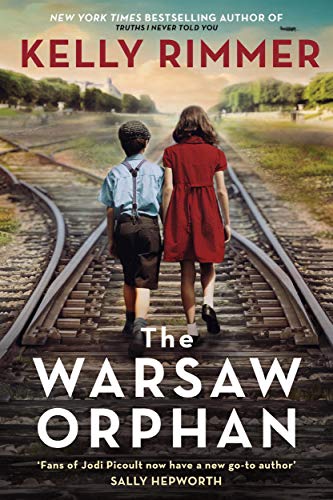

In the spring of 1942, young Elzbieta Rabinek becomes aware of the swiftly growing discord just beyond the courtyard of her comfortable Warsaw home. She has no fondness for the Germans who patrol her streets and impose their curfews, but has never given much thought to what goes on behind the ghetto walls that contain her Jewish neighbors. Then Elzbieta befriends Sara, a nurse who shares her apartment floor, and makes a discovery too awful to ignore, one that propels her into danger—and heroism. That’s the premise of The Warsaw Orphan (Graydon House, $17.99), and best-selling author Kelly Rimmer talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the historical underpinnings of her harrowing new novel.

YZM: Who was the real life heroine who inspired your novel? Where and how did you learn about her?

KR: Irena Sendler was a Roman Catholic Polish nurse and social worker. She coordinated a team of around two dozen people to rescue Jewish children from within the Warsaw Ghetto. Irena and her team smuggled children from the Ghetto through a variety of methods, including hiding small children in bags or coffins, or leading them through the sewers. Once outside, the children were placed with Catholic foster families to “hide in plain sight.” I first learned about Irena on a research trip to Poland in 2017 and immediately became fascinated with her.

YZM: Elzbieta says, “I couldn’t shake the feeling God was trying to tell me something.” Was it religious belief that inspired her determination and her courage?

KR: Like her family and indeed, most of her generation, Elzbieta was religious. Her determination and courage were inspired by both that religious belief and her family upbringing. Her role models were committed to helping those around them, even at great cost to themselves.

YZM: You say that there were Poles who despised the Germans and yet also despised the Jews and even blamed them for the invasion—can you talk more about this?

KR: The Nazis did not invent anti-Semitism. It had been a part of life in Europe for centuries, and it was alive and well in Poland long before the occupation. When the war began, the Jews became a convenient scapegoat for anti-Semitic Poles.

YZM: You describe a brutal gang rape; its victim later says that since she didn’t run, didn’t cry and didn’t fight, she was complicit in the attack. Can you elaborate on the shame, self-loathing and self-blame experienced by rape survivors? Do you think these feelings were more or less the same in the 1940’s as they would be today?

KR: In the cultural climate of the 1940s the stigma around sexual assault was extreme. Many women who were assaulted were never able to disclose what they’d survived—and there was no possibility of any kind of justice, these women knew the perpetrators would never face any penalty for their actions. But aside from those aspects, the tendency for survivors to blame themselves remains unchanged because it is a classic trauma response. In simple terms, the brain likes to convince us that we had power in situations where we had no power as a way of coping with a natural anxiety that a trauma may be repeated.

YZM: There are several harsh and painful scenes in the novel, and yet you’ve written an ending that can be construed as happy—why?

KR: I wanted to represent the way that Poland and her citizens rallied and rebuilt, and I’ve done this through my characters. They survive some of the most chaotic years imaginable, but they rebuild their lives and look to the future with hope, in the same way that Poland ultimately did.