“You are the motherfucking Antichrist!” For many moviegoers, their introduction to Paul Giamatti came in 1997, when the then baby-faced actor screamed this line at the shock jock Howard Stern. In Private Parts, Giamatti plays Stern’s boss at radio station WNBC, a tetchy asshole upon whom Stern bestows the memorable name “Pig Vomit.” Driven mad by Stern’s behavior—including phoning Mrs. Pig Vomit on the air—Giamatti’s character finally absolutely loses his shit. Held back by another executive, eyes bulging, Giamatti delivers the first diatribe in a career that will be filled with them.

The tirade has become Giamatti’s stock in trade. You want someone to erupt in a profane aria of rage? You need an actor who can sputter impotently while waving his arms? Better call Paul. As Marc Maron cracked in a recent podcast with Giamatti, it’s impossible to imagine a director being forced to ask, “Hey Paul, could you come in hot?”

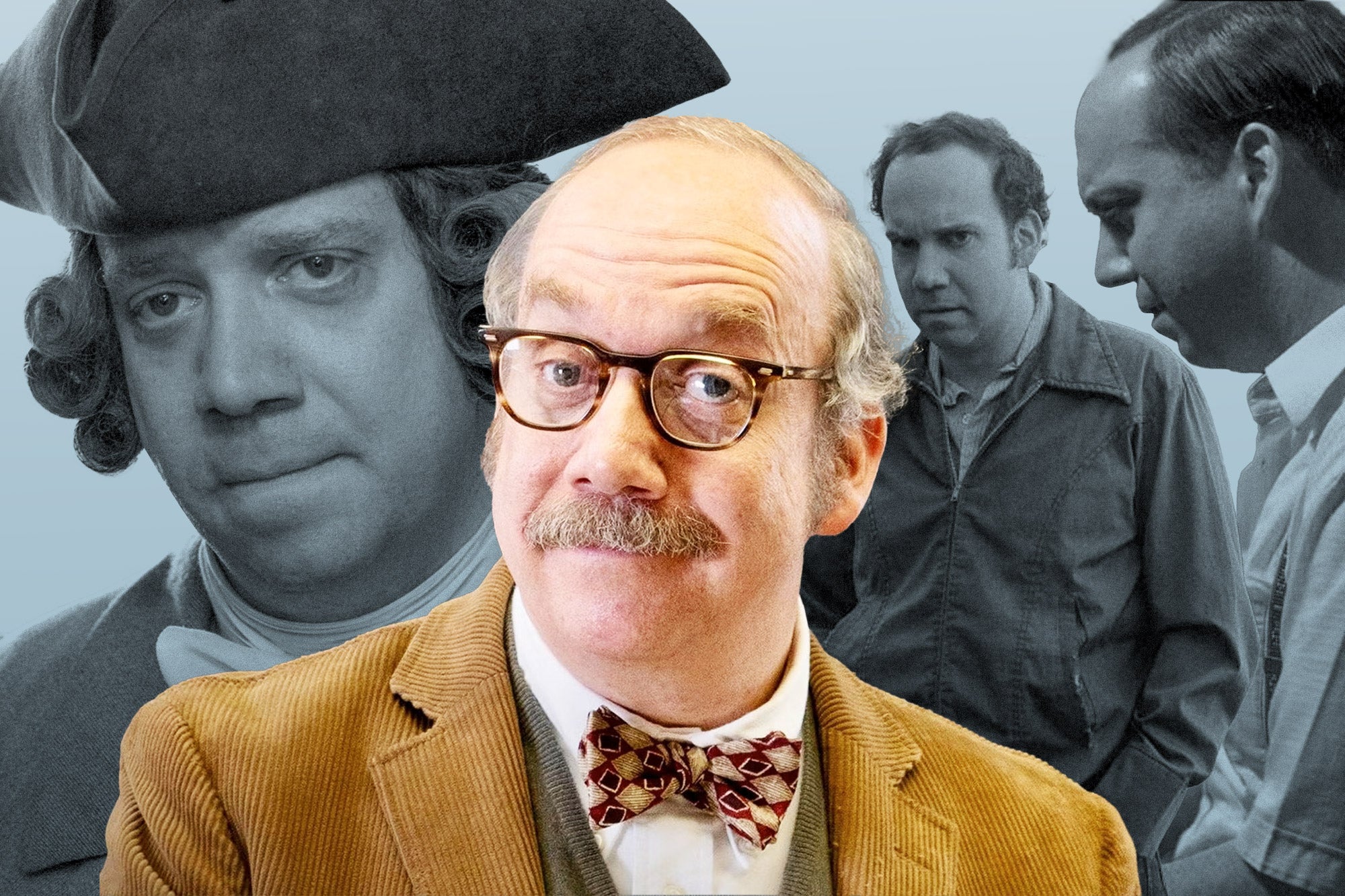

The Holdovers, Giamatti’s second film with director Alexander Payne—the previous one was 2004’s Sideways, which made the actor a star—seems at first to be tapping into an audience’s expectation for Giamatti’s onscreen explosions. The movie’s trailer even ends on a very funny freeze-frame of Giamatti about to shout, mouth wide open, eyes pointing two different directions. (The character, boarding-school history teacher Paul Hunham, suffers from strabismus, or eyes that don’t align with each other. Students and faculty alike call him “Walleye” behind his back.)

As Sideways did nearly 20 years ago, The Holdovers has put Giamatti in the thick of awards season. Back then, Payne’s movie was honored with five nominations, including acting nods for two of Giamatti’s co-stars, but Giamatti himself, who starred as a depressed writer and oenophile, was snubbed. Payne has said he believes the problem was that Giamatti made it look too easy—that voters assumed he was simply playing a version of himself. Giamatti, one of our best actors, has never been nominated for Best Actor: His only nomination, for Supporting Actor, came the year after the Sideways snub, for Cinderella Man—a classic “apology nomination.”

In The Holdovers, Giamatti is once again in his wheelhouse, playing another overeducated snob with a knack for vitriol. You can draw a line straight from “I am not drinking any fucking merlot!” to “Christ on a crutch, what kind of a fascist hash foundry are you running here?!” Though he’s on the record as saying his personal connection to The Holdovers’ setting—he attended a boarding school in New England—made playing Paul Hunham easier than usual, he also seems devoted, this time around, to making sure awards voters know what Paul Giamatti’s really like. Hence the explosion of Paul Giamatti onto your timeline as the notably cheery actor shows up everywhere: talk shows, podcasts, live events, trade-magazine roundtables, and even fast-food restaurants, burnishing his lovable-guy bona fides.

Assuming that a role wasn’t that difficult because an actor is “just playing himself” is, of course, a simplistic way to think about what acting really is. But making my way back through Giamatti’s three-decade screen career, I discovered that my understanding of the actor’s talent was similarly simplistic. He may be, as the New York Times put it in a recent profile, “one of cinema’s great talkers, often cited for dazzling flights of oratory,” but many of his most transcendent performances—including in The Holdovers—depend to an unusual degree on wordless anguish. Sure, you can cast Paul Giamatti as a motormouth, but his greatest power as an actor isn’t his mouth. It’s his soul—and the windows into it.

The prototypical Paul Giamatti character somehow straddles the worlds of the élite and the ordinary guy. Think of Miles Raymond in Sideways, whose two-manuscript-box novel and disdain for certain wine varietals can’t change the fact that he’s a depressed middle school teacher. Or Harvey Pekar in American Splendor, a file clerk from Cleveland who somehow ends up an audience favorite on Late Night With David Letterman. Or, for that matter, Paul Hunham, a classics teacher at a prep school who spends his days upbraiding the students for insufficiently appreciating Marcus Aurelius—though nearly every one of those “snarling Visigoths” has more money and influence than this former scholarship student ever will.

This genteel schlubhood is a unique reflection of Giamatti himself. He does not look like a leading man: He has neither the patrician elegance nor the meathead beauty of the sorts of actors who tend to headline movies. Instead, like the great character actor he is, he just looks like a guy. I wouldn’t go so far, as the headline of one 2007 interview did, as to call him “Mr. Potato Face,” but he could be anyone, from any time. “You can dress me as a short-order cook,” he told the Times, “or as a butler, or as the president of the United States in the 18th century, and I kind of look like I should wear the clothes.”

And yet Giamatti is a child of privilege whose father was the president of Yale for much of the 1980s and even, before his sudden death from a heart attack in 1989, served as commissioner of Major League Baseball. As a young man, Giamatti was himself one of those private-school “entitled degenerates,” a day student at Connecticut’s Foote School and Choate Rosemary Hall. He attended Yale, studying English—he remains a voracious reader and avid used-bookstore shopper—and returned there for drama school. Less than a year after graduating with an MFA, he landed his first high-profile role, as the buffoonish poet Ezra Chater in the 1995 Broadway debut of Tom Stoppard’s academic comedy Arcadia. His ascent wasn’t overnight: He did spend a few years between undergrad and drama school just getting by in Seattle, and that’s him in 1992’s Singles, making out with a girl in a café next to Kyra Sedgwick and Campbell Scott. But it wasn’t slow either.

It was in Private Parts, though, that a mass audience first encountered him—especially because Stern loved the performance so much that he spent 1997, the year of the movie’s release, campaigning on-air for Giamatti to win an Oscar. Pig Vomit is an outsider turned insider. He may be a top exec at a major-market radio station, but he’s no smooth-talking New York business star; Giamatti recalls that director Betty Thomas’ primary direction was to do “a stupid Colonel Sanders accent.” He’s someone who could have bonded with Howard Stern, a fellow nobody, but who instead sees his career scuttled by his inability to handle Stern’s mischief. After Stern delivers Pig Vomit’s comeuppance, the movie’s final credits are essentially scored to one more Giamatti eruption, an interview that ends with him yelling, “Howard Stern can kiss my ass in hell!” But the genius of the scene is not his final rage but Giamatti’s gradual descent from lofty attempts to be the bigger man—“I bear no grudge against Howard Stern”—into absolute despair. “I’ll tell ya, if Howard woulda listened to me, I’d still be up there in radio,” Giamatti says, his droopy eyes suddenly unable to meet the interviewer’s, before the expletives begin pouring forth.

The founding joke of Private Parts is that wherever Howard Stern goes, he drags everyone down to his puerile level: audiences, engineers, the culture at large. To see Giamatti, just out of Yale Drama and Arcadia, scream at the untrained Stern, who played himself, was perfectly appropriate. Throughout awards season, he’s been quick to credit Private Parts as more than the joke that some interviewers make it out to be. In this year’s Hollywood Reporter actor roundtable, he described the movie as a kind of wonderland after the strict regimen of Yale Drama. “I couldn’t believe I was being allowed off the chain like that!” he exclaimed. “I mean, look at me, man, I’m not a Shakespeare guy. And I get out and I get this opportunity to do something absolutely bananas. It spoiled me in a lot of ways. I thought, Oh, this is what it’s like, doing a movie?”

For the next few years, it wasn’t quite like that, doing movies, though Giamatti stood out in supporting roles in both indies (Todd Solondz’s Storytelling, in which he played a documentarian) and studio movies (he was the hapless control-room tech in The Truman Show). Certainly he got to go at least a little bananas in Man on the Moon, where he played Andy Kaufman’s partner in crime, Bob Zmuda. (The scene in which Zmuda tries to imagine Kaufman’s cancer diagnosis as an opportunity for further Kaufmanesque hijinks is a real kick in the pants.) And it’s hard to begrudge the guy his delight in getting to play an orangutan in Planet of the Apes. Often, though, Giamatti found himself portraying hapless Everymen in dull dramas. How did he end up singing “Try a Little Tenderness” with Andre Braugher in Bruce Paltrow’s execrable Duets? An actor’s gotta do what an actor’s gotta do.

In the early 2000s, two films worked out ways for Paul Giamatti to be a leading man, and in doing so changed his career trajectory. The first was American Splendor, the adaptation of Harvey Pekar’s autobiographical comics. Giamatti is a revelation, thanks to his unwavering commitment to playing Pekar as a gigantic pain in the ass. Giamatti shuffles and grumbles his way through the movie, his eyes darting this way and that and bugging out in moments of indignation. Even by the movie’s end, when Pekar has supposedly found some success, a wife, and an adopted child, Giamatti’s expression upon watching his family ice skating looks less like contentment than constipation. But he can’t take his eyes off them.

Giamatti won a 2003 “breakthrough performance” award from the National Board of Review for Splendor, a prelude to the accolades he’d garner for the next year’s Sideways. His performance as Miles is a sort of inverse of his performance as Pekar: Instead of slowly letting us see the kindness hidden under his character’s raging weirdo persona, Giamatti plays Miles as a warmhearted intellectual whose flaws and failures bubble up to the surface as the movie goes on. At first he’s merely the straight man to Thomas Haden Church’s flamboyantly handsome Jack, whose upcoming nuptials the two are celebrating with a trip to Santa Ynez wine country. Jack wants to get laid, as quickly as possible, before he’s tied down, while Miles just wants a nice time with his friend.

But then Miles steals $900 from his own mother. As the movie goes on, we get to see both Miles’ best side and his worst. Giamatti’s scenes with Virginia Madsen—who, like Church, was nominated for an Oscar while Giamatti was overlooked—are little marvels of empathy, as we see Miles discover, to his own surprise, that he can be kind, charming, and interested in someone else. Yes, Giamatti talks, but he also listens, and the film’s editing makes sure we see him listen. Then, when it all falls apart and the account comes due for his lies and elisions, Giamatti’s performance turns sublimely comic, climaxing with his apocalyptically gross overturning of a winery’s spit bucket into his own mouth.

More than one online commentator jokingly compared the end of Sideways, when a crestfallen Miles takes his prized ’61 Cheval Blanc to a burger joint and drinks it out of a Styrofoam cup, with the real Giamatti’s post–Golden Globes visit this month to an In-N-Out, statue in hand. And it’s true that something about Giamatti’s hangdog mien blurs the line between triumph and defeat. Those two guys—Miles at his lowest, Giamatti riding the waves of victory—don’t look that different from each other.

In the 20 years since Sideways, it’s been rare for Giamatti to topline a movie. (A couple of worthwhile exceptions: Barney’s Version, a fantastic adaptation of the Mordecai Richler novel—Giamatti’s performance won him his second Golden Globe—and Tom McCarthy’s pre-Spotlight drama Win Win.) Giamatti has said he doesn’t really believe himself to be a leading man—that he enjoys being the “central character on an ensemble” but that he finds the idea of carrying a movie intimidating. “I watched Denzel Washington in Equalizer III,” he told Dax Shepard on a recent episode of Shepard’s podcast, “and I thought: I could never do what this guy does.”

In movies, for the most part, he’s remained a character actor, the guy you bring in for a couple of scenes to support the story and the stars’ performances. Such roles nearly always rely on a certain sort of typecasting, so it’s no surprise that a lot of these roles resemble one another. What’s Giamatti’s type as a character actor? He said it himself, describing his first elementary-school play: “We did The Pied Piper of Hamelin when I was in the fourth grade,” he told Maron. “I played the corrupt mayor who rips the Pied Piper off. I’ve kind of been doing the same thing ever since: The small man who wants the power but he can’t really handle the power.” Sometimes the small man is nonetheless a force for good, as in Cinderella Man, that one Oscar-nominated role, the fast-talking promoter who helps Russell Crowe’s boxer out of the gutter. More often, he’s despicable: the slyly menacing manager in Straight Outta Compton; the slave trader in 12 Years a Slave, slapping the haunches of the human beings he’s selling as he dickers over price; the Rhino in the terminally silly The Amazing Spider-Man 2, a role that I hope paid for a lot of used books.

One imagines he’s been less anxious to play leads in movies because over the past two decades, television has given him some juicy roles. He won an Emmy for the miniseries John Adams, playing the second president with an orotund Colonial accent and a bottomless well of willful pride—a president who still wants to look smarter than everyone else. He was nominated for another Emmy for a guest appearance on Downton Abbey before settling into seven seasons of the Showtime series Billions, another project that puts Giamatti’s class confusion to good use. U.S. Attorney Chuck Rhoades may be wealthy and powerful, but he can never quite catch up to his archnemesis, the ultrarich hedge fund manager played by Damian Lewis. That frustration fueled Giamatti’s performance for 84 episodes in a show that was enjoyably hard-driving—a series whose idea of a subtle character note was having the domineering Chuck regularly get whipped by a dominatrix. (Giamatti, whose 1997 marriage ended in divorce, has been dating Clara Wong, who played the dominatrix, since at least 2019.)

Of all of Giamatti’s roles in the decades between his Pig Vomit breakout and his current pinnacle, it’s one of Giamatti’s most obscure movies that sticks with me the most, an unusual 2009 science-fiction film called Cold Souls. A kind of Charlie Kaufman–meets–Nikolai Gogol experiment directed by Sophie Barthes, Cold Souls stars Giamatti as Paul Giamatti, the movie and theater actor, who’s suffering a crisis of the soul. Tormented during rehearsals of Uncle Vanya—“What happened to your sense of humor, for Christ’s sake?” his director asks him—a desperate Paul contacts an unusual company on Roosevelt Island, a soul-extraction concern, which will remove your soul and keep it in storage for as long as you need.

“I don’t need to be happy,” Paul tells the clinic’s slick representative, played by David Strathairn. “I just want to not suffer.” When his soul is removed—it looks like a chickpea—Giamatti, the actor, does something remarkable to Paul, the character. His soul, honest to God, disappears. Rehearsing a Vanya speech that’s long stymied him, the new soulless Paul delivers the lines as light comedy, technically perfect, wonderfully shallow, and without the faintest sense of an inner being. It’s among the sharpest scenes I’ve ever watched about the work of acting and the ineffable ways it succeeds and fails.

Paul Giamatti has long been concerned with who Paul Giamatti really is. “I watch myself sometimes on a talk show and I go, ‘I don’t believe that guy at all,’ ” he said to Maron. “Then I’ll see myself in a movie and I say, ‘Oh I believe that.’ ” He laughed, a little uncertainly. “I should be more convincing as me!” Watching Cold Souls, where Paul Giamatti erases the life from his eyes to play a different Paul Giamatti, I became convinced that no actor could have performed this role in quite this way, because—it sounds nuts to write it in an otherwise normal-sounding essay—no one has a soul quite like his.

A.O. Scott did not love Sideways. In an essay published just a few years into his tenure at the New York Times, Scott poked at why he felt this “funny and observant” film had become “the most overrated movie of the year” by his fellow critics. His conclusion was ingenious: Critics love Sideways because Miles Raymond is, above all else, a critic. The difference between Miles and his friend Jack, Scott wrote, is

the difference between a sensibility that subjects every experience to judgment and analysis and a personality happy to accept whatever the moment offers. When they taste wine, Jack is apt to say “tastes good to me,” and leave it at that, whereas Miles tends not only to be more exacting in his judgment (“quaffable but not transcendent,” which is about how I feel about Sideways), but also more prone to narrate, to interpret—to find a language for the most subtle and ephemeral sensations of his palate.

I might quibble that the reason critics loved Sideways wasn’t that they loved seeing themselves onscreen but that they felt exquisite pain upon seeing themselves so expertly skewered onscreen, but I think Scott’s basically right. I returned to this essay, nearly 20 years later, because if there’s one thing that this awards season’s flood of Giamattiana has taught me, it’s that Giamatti, too, the old English major, is a critic. He’s a critic of earthy tastes: He loves genre fiction, old sci-fi and mysteries, and one of the joys of the actor’s many recent podcast appearances has been hearing him weigh in, more than once, on the pleasures of The Equalizer III. A critic, of course, has to be a good communicator—has to be able to use words to convince, to convey, to persuade. But a critic also has to be a good watcher.

Listening to Giamatti on the awards circuit gives me the same idea that watching Giamatti in movies gives me: He’s not that different from me. He’s a critic, an enthusiast, nice but also a little bit grumpy, appropriately skeptical. That relatability is a forceful tool for an actor, and one of Giamatti’s superpowers is that he’s relatable both to critics like me and to non-critics, the Jacks of the world, the ones who watch a movie and say, “That’s good acting.” After all, Sideways was a hit with more than just critics, earning more than $100 million on a modest $16 million budget and remaining in theaters for more than six months.

I also thought of Scott’s Sideways essay because I just watched Tamara Jenkins’ 2017 Private Life, the best film of Giamatti’s later career until The Holdovers, and laughed out loud when Giamatti appeared—because in the movie he is a dead ringer for A.O. Scott. The hair, the glasses, the clothes, the temperament: It’s uncanny. (In his rave review of the film, Scott mentioned in passing that watching Giamatti made him feel as though he’d “accidentally walked past a mirror.”) But if you can set aside the issue that Giamatti has been styled to appear identical to a prominent film critic, this performance points to another way forward for Giamatti as a lead actor, whether he wants to think of himself that way or not.

Richard, the former theater director played by Giamatti, takes a back seat throughout the movie to his wife, played by Kathryn Hahn. After all, she’s the one going through fertility treatments, but also she’s a bigger personality, needy and prickly, and Hahn’s is the bigger performance. Giamatti underplays throughout Private Life, gifted with a script that allows him to develop his character through silence and judicious voice-of-reason interjections. He’s a bundle of nerves, but he keeps those nerves under wraps for almost the entire film. And the payoff is enormous, in a final scene—one I won’t spoil because I really want you to see the movie—that depends entirely on Giamatti’s unspoken choice to get up and move.

I think it’s in part thanks to that beautiful performance that in recent interviews, Giamatti has been gently pushing back against the idea that his motormouth is necessarily his greatest tool. When Maron made his crack about Giamatti “coming in hot,” the actor demurred, insisting that more and more often, his impulse is to underplay. “As I’m getting older,” he continued, “I want to be quieter. I just want to sit and be quieter.”

Its marketing campaign aside, The Holdovers gives him that opportunity. More than you might expect, it’s a still, sorrowful movie, one that’s only occasionally punctuated with shouty interludes. As in Sideways, Giamatti is the lead, but he’s surrounded by colorful, crackling characters for his sad sack to bounce off: rebellious teenager Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa) and mourning, sardonic cook Mary Lamb (Da’Vine Joy Randolph).

I’ve wondered what it is that has made this performance break out, giving Giamatti his best chance at an Oscar in a nearly quarter-century career, during which he’s been generally considered one of the best actors alive. I think it’s the movie’s embrace of Giamatti’s powerful stillness. After watching The Holdovers, you’ll remember the many colorful insults, the stupid way he runs down a hall, the scene of him drunkenly farting in his boarding-school cot. (What other leading man in America would play that?) But while you’re watching The Holdovers, you’ll find yourself mesmerized by Giamatti’s watchfulness, his silence, and his desolate loneliness.

A scene right in the middle of the movie, at a Christmas Eve party, epitomizes what Giamatti does best. As in Sideways, his character finds himself surprised to be engaged in a warm conversation with a woman, the school’s office administrator Lydia, played by Carrie Preston. As they speak, he allows himself to hope, despite not exactly having “a face forged for romance.” Then Lydia’s boyfriend arrives at the party. After he sees her greet him with a kiss, Giamatti turns back to the camera, and though he’s hardly uttered a word, it’s as if he’s an entirely different person. I was reminded of the color-timing effect Peter Jackson used in The Fellowship of the Ring to show the light fading from Boromir’s eyes when he dies.

In The Holdovers, of course, only one of Paul Giamatti’s eyes is a special effect, and at first the cast and director played coy about how the illusion was accomplished. “It’s just movie magic,” Giamatti told one interviewer. The movie’s credits include a “contact lens tech,” and in later interviews they’ve fessed up, but for a while it seemed to please them to pretend that maybe, just maybe, it was a thing Giamatti was just somehow doing, live—that he taught himself to point his eye in a different direction. (“That’s good acting!”)

I found myself touched by this quirk of character, which might be an impediment to some performers but which Giamatti treats as a sort of gift. Yes, by sticking a giant contact in Giamatti’s eye, Payne is taking away one of his lead actor’s greatest tools. But the “lazy eye” works a kind of magic in the movie, in part because, I’m pretty sure, Payne playfully switches which of Giamatti’s eyes sports the effect throughout. (Note which eye Hunham points to for Angus’ benefit in the hallway, and then note which eye looks at the road as he drives away.) In every shot, the eye makes itself known, literally glaring, an ever-present leavening agent to serious scenes, an ever-present amplifier to Hunham’s fury. As Giamatti has done his whole career, the eye blurs the lines between the sad and the comic, between the passionate outburst and the hapless pratfall. Half the windows to Paul Hunham’s soul don’t quite open the way they’re supposed to, but in the performance that I’d bet is going to win him the Oscar, Giamatti still lets us see right through.