Was James Bond the Result of Ian Fleming's Midlife Crisis?

A new book about the novelist's Jamaican retreat, Goldeneye, suggests an indulgent and escapist lifestyle inspired a character who embodied a stubbornly anachronistic ethos.

When MGM rebooted James Bond with the origin story Casino Royale in 2006, Bond got younger—but had never looked older. Though some of Bond’s overall fatigue was due to the casting of Daniel Craig, a 38-year-old with a rugged physique and craggy facial features, in the title role, much was the result of a storyline that explained Bond’s character with a sobering tale of childhood woe and formative romantic tragedy. Pierce Brosnan, after all, had been 42, Timothy Dalton 43, Roger Moore 46: yet none of these Bonds had ever appeared so beat-down, so weary about carrying the weight of the world on their shoulders, or, by Craig's own admission, so serious.

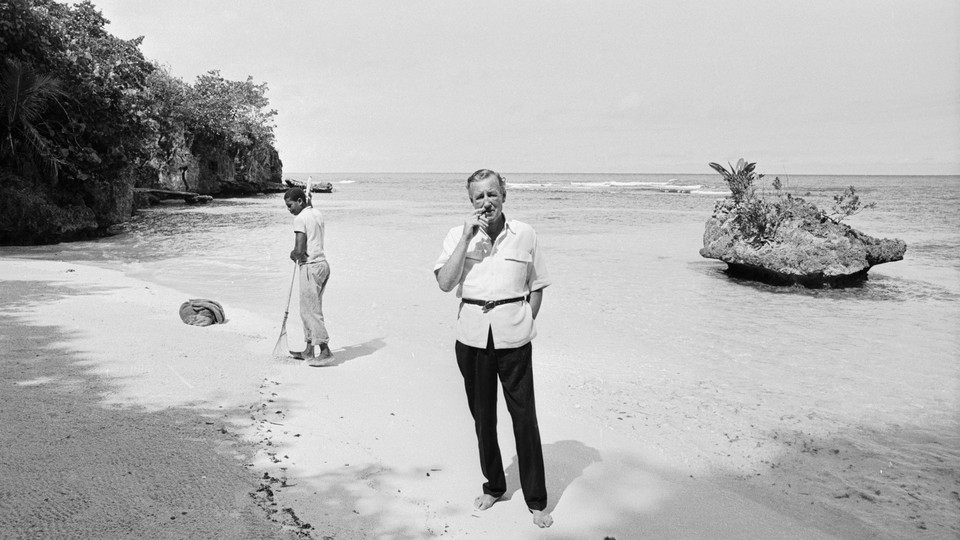

But if Craig's Bond-in-crisis diverges from the movie franchise's campy past, it may be pretty faithful to the spirit of the original books. That's one takeaway from Matthew Parker's Goldeneye, Where Bond Was Born: Ian Fleming’s Jamaica, the first book to explore the north-shore estate where the author and former intelligence officer Ian Fleming spent two months each year and wrote all the Bond books. The purchase of his tropical lair, the retreat from society, the way Fleming spent the latter half of his life there—these are all apparently telltale signs of a man who just can't handle getting older. What Parker's new book shows is how much that crisis latched itself onto James Bond, and how the defiant fantasy he provided against decline both restored Fleming and gave life to an immortal franchise.

Ian Fleming was 35 when he first visited Jamaica for a conference concerning German U-Boats—though, to hear Parker's account of it, the island appealed to his boyish side. Fleming loved Jamaica for its recreational activities, its Caribbean folklore (basically, his belief that it contained lots of buried treasure, informed by his terrible “four-penny horrors” habit), and the kinglike reception he got from the locals merely for being British (he arrived at the tail end of its time as a crown colony). How he came to establish an estate there was equally quixotic: At the end of the war, Fleming told his friend Ivar Bryce, he would relocate to Jamaica to “swim in the sea and write books.”

That he actually did so seems like something right out of Bondian fantasy, which in turn seems inspired by his annual stays there. Three years later, Fleming managed to secure two months of paid leave each year from his job at the Sunday Times and commissioned an ascetic, box-like house near Oracabessa that he named "Goldeneye," after a wartime operation in Gibraltar. It may have also come from the fact that Oracabessa means "Golden Head" in Spanish, and that Fleming had enjoyed Carson McCullers' novel Reflections in a Golden Eye. In the early years, he spent his Jamaican vacations fishing with harpoon guns and steel tridents (not unlike the unique, yet totally preposterous, underwater battle in Thunderball). He tempted fate by carrying on conspicuous affairs with many of the island’s expatriate British elite, most of whom were taken (his most important mistress, Anne Rothermere, was married to a viscount who was the proprietor of the Daily Mail). He purportedly drank a bottle of gin a day and insisted his staff call him “the Commander.”

Having established such an ideal getaway location, Fleming didn't have to imagine too hard when he first designed Bond. The spy's name, famously, was swiped from the author of The Birds of the West Indies, which he kept on his shelf at Goldeneye; Domino (Thunderball) and Solitaire from (Live and Let Die) came from the names of tropical birds; Vesper (Casino Royale) referred to a cocktail of frozen rum, berries, and herbs Fleming was served at one of Jamaica’s Great Houses. The glamorous details were exaggerated and improvised, and the political reality of Jamaica’s brewing independence movement distilled. At the beginning of Dr. No, Bond, put off by the unfriendliness of the locals, predicts the Queen's Club will soon be "burned to the ground"—a threat that's extinguished when Bond saves the island from an outsider, a horrendously racist villain identified as a "Chigro."

Parker downplays the blatant offensiveness of the Bond books—to various ethnicities, women, carnivorous sea creatures, Americans—by making the point that Fleming was prejudiced against anyone who wasn't British. It's in service of an interesting thought: Bond's blinkered machismo, he suggests, resulted from Fleming's own fearful preoccupation with the decline of his youthful hopefulness. Fleming always told reporters that he wrote the first Bond book, Casino Royale, to avoid “the hideous spectre of matrimony.” Parker proves it was also a premeditated effort to bankroll life after marriage, distract the writer from his declining health, and willfully combat Britain’s reduced, post-WWII power.

In his December 2014 cover story for The Atlantic, “The Real Roots of the Midlife Crisis,” Jonathan Rauch argues that the dominant one-off “crisis” narrative doesn't reflect the trajectory of happiness that most people experience over the course of their lives. Recent research supports the idea of a U-curve where satisfaction dips around middle age, but ultimately enjoys an upswing toward the end. The notion of a "crisis," he notes, may simply be an excuse for bad behavior.

Whether Fleming was truly experiencing a midlife crisis before the term was even coined is unlikely. Bond’s staying power, nevertheless, has its roots in the same fantasy of defiance. As Fleming was in personal decline—his 70-cigarettes-a-day habit had taken its toll—Bond was on the rise as a breakout literary hit in England, and became a special favorite of President Kennedy. Though Bond suffered his share of seemingly autobiographical health issues—in Thunderball the spy begins to acknowledge that his heavy drinking may be a problem, and by On Her Majesty’s Secret Service he's definitively in the throes of alcoholism—he always comes out on top. If anything, Bond gave Fleming the excuse to indulge in the same socially acceptable antisocial behavior, consumerism, and irresponsibility as his fictional creation.

Though Parker doesn’t go into it, the immortality of the Bond franchise may have something to do with this seductive myth. Reading a Bond book, going to a Bond movie—both provide allow people to indulge in the idea that a middle-aged man might be capable of pulling off spectacular physical feats and seductions; that old British social mores are still posh and powerful; that nations stand a chance against prescient, terrorist-like organizations such as SMERSH and SPECTRE. Jamaica was the final escape from crushing reality, much like the franchise continues to be today.