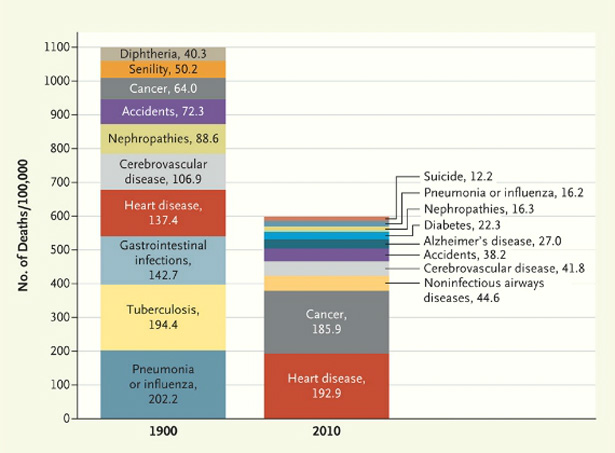

Chart: What Killed Us, Then and Now

The New England Journal of Medicine combed through 100 years of history to produce a single, awesome graph.

Via The Washington Post's Sarah Kliff comes this incredible chart from the New England Journal of Medicine comparing the reasons we die now to the way Americans went to their graves a century ago:

The chart ranks the top ten causes of death for each year. In addition to the remarkable decline in mortality overall, it's also noticeable how heart disease and cancer have surged to become two of America's top killers. In 1900, cancer and heart disease accounted for 18 percent of all deaths. Today, that figure's jumped to 63 percent. In addition to being responsible for a greater share of deaths overall, the absolute number of people being killed by these chronic conditions has also grown, from 201 people out of every 100,000 in 1900 to nearly 380 per 100,000 today.

Part of the increase can be traced to our increasingly sedentary lifestyles. But we shouldn't forget that vaccines, regular screenings, and other advances in medicine have drastically reduced the incidence of other ailments that once sealed many an American's fate. The way we've chopped up and redefined some conditions has also changed the country's death profile. There's the seemingly endless "discovery" of new diseases. And it's worth pointing out that the rise of cancer and heart disease, as illnesses that generally affect people late in life, are themselves an indicator of improvements in a society's overall health. The fact that more people are living long enough to be diagnosed with cancer says something about how far we've come.

What we get from each cross-section of death isn't just a snapshot of what's objectively happening to people; it's also a reflection of our attitudes toward specific illnesses. The authors explain:

Changing environmental and social conditions can increase the prevalence of once-obscure ailments (myocardial infarction, lung cancer, kuru, and "mad cow" disease). New diagnostic technologies and therapeutic capacity can unmask previously unrecognized conditions (hypertension). New diagnostic criteria can expand a disease's boundaries (hypercholesterolemia, depression). Changing social mores can redefine what is or is not a disease (homosexuality, alcoholism, masturbation). New diseases can emerge as the result of conscious advocacy by interested parties (chronic fatigue syndrome, sick building syndrome). HIV-AIDS alone demonstrates many of these modes of emergence.