The last time I interviewed Russell Brand was in 2008, around the time of Sachsgate, and he was a handful. When I asked him, as a joke, if he was going for world domination, he replied, “Yes, that is what I will do. What am I going to stop for? I’ll just carry on until there’s nothing left.” Nine years on, he has changed in some ways, and in others, not at all.

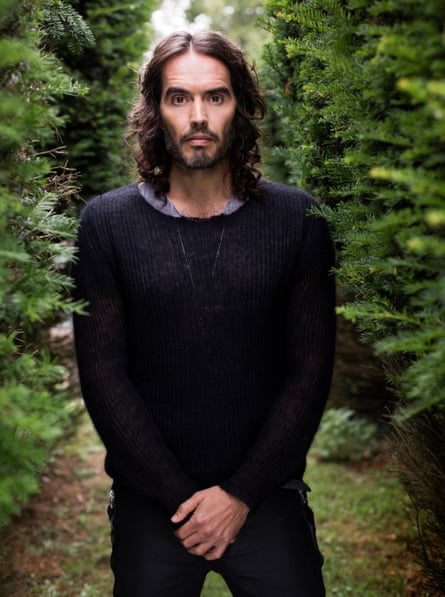

He still looks amazing: tall, long-haired, Gypsy-George-Best handsome; a dandy highwayman in black leather trousers and goth jewellery. His mind still fires faster than a machine gun, and his speech is just as packed with flowery words and detailed explanations, peppered with references to what he’s read (Jung, Harari, life coach Tony Robbins). And he’s still funny. But Brand is different. His ego is less all-consuming. In 2008, he was difficult with the photographer (not today, he’s fine) and, during our chat, he kept moving his head so that, even when I tried to glance away, he was constantly in my sight-line. It was as if my eyes were the spotlight and his face had to be in it. No more.

“Yes, I’m less mad now,” he says, when I mention this. “I was a needy person. I mean, that condition abides, but I manage it better now, I think.”

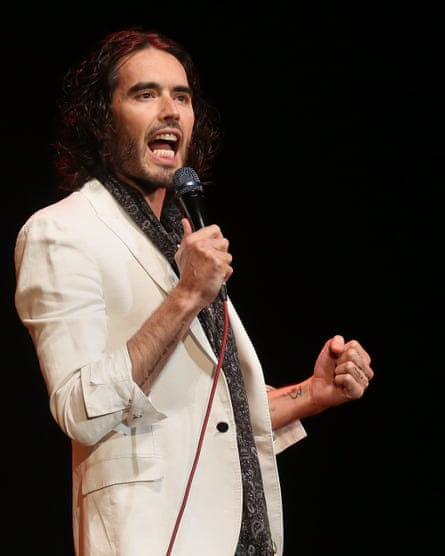

Back then, he was also very much a girl-hound – “I love fucking,” he told me. “My house has a hot tub for damned good reasons, and none of them spiritual.” But these days he’s settled, living in the countryside with his new wife Laura Gallacher (sister of Sky Sports presenter Kirsty), baby Mabel, two cats, a brace of chickens and a “maniac” dog. Having burned through his marriage to Katy Perry in two years, and dated Jemima Khan, his relationship with Gallacher, on and off for years, is now settled and domestic. Career-wise, he’s still a standup – he’s on a 71-date tour that will take him into 2018 – but seems to have stopped acting, and has shifted a lot of his public work to activism. In 2014, he began posting The Trews, his political YouTube show, garnering more than 1m subscribers. He’s now studying for an MA in religion in global politics at SOAS University of London. He hosts a wordy, thought-provoking podcast, Under The Skin, where he talks to academics, politicians and writers about contemporary ideas. Is this all less mad? It’s an effort to be more serious, certainly, though his daft performer’s instinct can send him off course in search of the joke, so that he gets ridiculed on political TV shows.

Anyhow, all of this newfound stability and seriousness, according to Brand, is due to his 12-step recovery programme. Though he’s been off drugs since 2002, Brand’s addictive nature meant that his attitude towards sex, porn, money, relationships, food, fame – everything, really – was abnormally compulsive and got him into trouble. So, for the past four and a half years, he has been applying the steps across the whole of his life. He has found this transformative, and thinks many others would, too. In fact, he wants us all to be 12-steppers. “I think that this ideology needs to be proliferated,” he says, “and I think that the more access people have to it, the more people could use it. I’m fascinated by its potential.”

We are chatting in a beautiful hotel in the countryside west of London, not far from where he lives. On a side table, several necklaces have been laid out for Brand to choose from for his photo shoot. A hotel worker delivers avocado on toast while we talk before a vista of perfectly appointed gardens. It’s a setting unlike most representations of an AA meeting that I’ve seen, but let’s talk the 12 steps. The 12 steps form the basis of Alcoholics Anonymous and of all other associated groups (Narcotics Anonymous, Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous, Gamblers Anonymous, Overeaters Anonymous). The first step is an admission of powerlessness over the thing to which you’re addicted. The steps aren’t hard to find, but there is a lot of related literature, too, and though this isn’t a secret, it tends to be passed only between those who attend AA meetings. This isn’t enough for Brand. He is so evangelical about the steps that he has rewritten them, in Brand-speak, for his new book, Recovery: Freedom From Our Addictions.

Aside from the foreword and conclusion, Recovery has 12 chapters, one for each step, and with each Brand takes the step’s essence, rejigs it, and uses his own life to explain what he means. So the AA step one, “We admitted we were powerless over alcohol, that our lives had become unmanageable”, becomes, in Brand’s reworking, “Are you a bit fucked?” AA’s step six, “We were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character”, becomes: “Do you want to stop it? Seriously?” You get the gist.

The book is entertaining and easy to read. There’s a chapter about Brand’s daughter’s birth that is graphically real and very moving: “As if touched by the finger of creation, her eyes flash open and life possesses her and exudes from her. Like seeing behind the curtain as she moves from life’s shadow to life.” Still, I’m not sure how necessary the book is – surely, the existing steps literature works fine – so who is it for?

“For people who have drug and alcohol or sex or food issues, but find some of the literature too clinical, or Christian,” Brand says. “But also, I think it could be applied as a sort of model, because now my lens for living is this. I think it’s universal.”

He tells me about a professional, non-AA meeting he recently attended. He asked if anyone felt they were out of control over anything, and one person mentioned their phone use, another how possessive they were about their friends, another how they behaved when dating. These are the people he wants to read his book, he says; addiction is on a sliding scale, and we all, to a greater or lesser degree, display signs of addictive behaviour. “Addiction is just an extreme behavioural pattern, and we all have patterns.”

He may well be right: I just question whether Brand is the person to take us all through the steps. Also, there’s a point, surely, to the anonymous bit of AA? If the support groups aren’t anonymous, then people don’t feel free enough to talk honestly.

He disagrees. “That anonymity was necessary at the inception, I think, precisely because it was 100 years ago [AA started in 1935; the steps were written in 1939], and there were different social attitudes about chemical misuse and alcoholism. The fellowships themselves had a fragility, and needed to be protected from the idea that anyone could claim to be a spokesperson for them. But I think such anonymity now is preventing a technology that people would benefit from being proliferated.”

He points out how easy it is to order drugs, or indeed anything else, from the internet; how consumer culture is designed to make us think that if you don’t feel good, “there is something you can get to make you feel better and you can probably buy it”. Whether it’s the bump of serotonin you get from a heart on an Instagram post, or the one you get from winning an eBay auction, today’s culture is designed to make you temporarily euphoric through consumption, rather than fully happy because you have changed your habits.

“We’re reaching saturation of consumerism, and the antidote to all this needs to be accessible as well,” he says. “In a way, this book is a progression of the last book I wrote.” Revolution, Brand’s last book, was his call for a political revolution, based on destroying capitalism and getting transcendent instead. (Spoiler: it didn’t work.) John Lydon called it idiotic, and even his friend Noel Gallagher, on hearing that Brand was writing another book, said, “What’s it going to be called this time? The Revolution That Never Took Place?” Still, Brand is persistent. “There’s an ongoing sense that this isn’t working. Really, I’d like to address the emotional and spiritual causes of dissatisfaction on a personal level.”

Ah, the Big Idea. It’s easy to forget, when presented with a comedian who threw away several careers, not just his own, by leaving off-colour messages on the answerphone of a Fawlty Towers star, that Brand has always been interested in the Big Idea. In 2008, he said this to me: “The material world is a transitory illusion, and if it is, why organise your life around the systems that it imposes? Particularly if those systems have negative consequences for huge numbers of people, and the planet itself. I wonder if there are ways that that can change... and I don’t mean normal things like, let’s wear a ribbon – I mean the entire economic structure of the planet or the way we look at religion.”

He’s still thinking along those lines. His Under The Skin podcast is an attempt to get clever people such as Naomi Klein, Al Gore, Adam Curtis and assorted professors to explain their own Big Idea and unpick the systems we take as set in stone, whether those systems are economic or social. He’s searching for the meaning underneath. Brand used to be a Buddhist; now, he believes in a higher power, and the steps are his new faith.

“There was an important job that religion was doing,” he says, “but because of the bigotry, the outdated acculturation of the time of its construction, the casual and unaware attitude towards gender and race, we have, possibly quite rightly, rejected it. But the secularisation, the materialisation, the individualisation of the way we see the world now excludes us from a life that has meaning. And I don’t think pop culture can fill that gap any more. I don’t think art can do it any more. I think things are getting too serious. People need to be able to connect with something that is essential and beautiful and valuable and true.”

This is pretty much what he was saying 10 years ago, I feel. It’s just that, this time around, Brand’s solution is different. For him, the 12-step programme “has the seeds in it, it has the code”. The meaning of life, the Big Idea. It may well do – the 12 steps have saved a lot more lives than me – but I have another issue with Brand’s book. AA and its associated groups are all free. Though there are those who pay to go into rehab, there are many more who just turn up to meetings and pay nothing at all. Brand will be charging money for his book. How much of his profits will go to AA?

“Some I’ll give to abstinence-based recovery,” he says, “but I’ve not made a devout vow to be a mendicant, you know? My hope is that I’ll become a person that lives entirely charitably and entirely philanthropically and entirely spiritually. And a significant percentage of what I earn – 10, 20% – goes into that kind of thing already; it has done for a little while. Aside from that, there is a 12-step message in this book, but it’s coming through me, it’s using me. It’s still me.”

Exactly, I say. The book is about you. It has a picture of you on the front.

“I know that. I know I’m narcissistic. I know I’m no different from anyone with ego problems, showing off, going, ‘Love me, love me, adore me, give me attention’, but it ain’t just that. It’s something else. And that thing, I’ve got to do something with it.”

I believe he believes this. But I still think it’s his ego. Brand is working hard on his narcissism, but not enough to stop him thinking he can save us all. And not enough to stop him making money by rewriting the programme that saved his life for free. Still, here we are. Before he decided to work the 12 steps throughout his daily existence, Brand spent a lot of time searching for how he should live. He read innumerable self-help books, hoovered up philosophy, puzzled away. He has the phone number of Eckhart Tolle, author of The Power Of Now, and for a while would phone him up – “This living saint!” – with his love-life problems. One time, Brand was banging on about the troubles he was having with his then girlfriend, and at the end of his love tirade, Tolle said, deadpan, “Well, perhaps the relationship will work out. And then both of you will die.” This made Brand laugh, and makes me laugh when he says it.

His personal quest means he’s gone through umpteen therapists, regaling each with his admittedly eye-popping life story. It got to the point where it would almost be a performance. He would rattle through being an only child, his mum getting cancer three times, being sexually abused by a tutor, his relationship with his macho stepdad, his sexually profligate dad who took him to Thailand and ordered three prostitutes (two for him, one for 16-year-old Russell), his problems with crack, heroin, with cutting himself, with sex, with food. The therapist he liked most listened to it all and said, “Yes, but Russell, what is it? What. Is. It?”

What is it? In his book, Brand recalls a day he went to London to meet a theatre director. His tale is a litany of minor discomforts, the worst of which is that his phone runs out of juice and he can’t get a cab. For Brand, though, this series of very small annoyances is almost catastrophic. He cannot cope. His mind fires all over the place, taking him back to when he had nothing, flicking over his junkie past, speculating about strangers’ jobs, then painfully picking through small talk to a moment of joy with, of all people, the actor Zoë Wanamaker. As I read it, I was reminded that, in addition to his addiction problems, Brand has ADHD. It must be exhausting being him.

In that chapter, what he’s trying to demonstrate is how emotional we can be when life bashes us about, but also how the steps can provide a form of mindfulness, a technique to deal with the mania and loneliness and resentment that can easily sweep through our system and knock us off course. Or, at least, knock him off course. What his story makes me feel is that I’m not like that; we all have days when everyone and everything is a wind-up, but usually I manage to shrug off the externals and get on with my life. “Yes, I think addicts are outliers, we’re so jittery about the external world that we’re like, ‘Fuck this, I’m going to find something to medicate and alleviate this.’ I know I’m a nutter.”

No wonder he lives more quietly now, though quiet is a relative term. He’s still making the odd Trews show – he’s just put one up about Sinéad O’Connor, sympathising with her mental illness – plus there’s the podcast, his MA, the book, and he’s doing three standup gigs a week. Performing comedy means his adrenaline is all over the shop; up late and wired, he has to sleep more during the day to keep himself steady. He’s trying hard to be reasonable, because “the more I hear myself being reasonable, the more difficult it becomes to transgress those rules and my own behaviour”.

And he likes living quietly. “I’ve never had domesticity before. Most of my life has been an extension of the grandiose idea of what glamour would look like if it had to have a kitchen. And I feel sometimes like a refugee in my house with this woman, this calm, beautiful woman, who in the most beautiful way possible doesn’t care about what I do. She’s not interested, in the most delightful way. ‘Oh, that sounds nice.’”

He’s enjoying having a daughter, too, though the lack of control takes some getting used to. He might have joked about raising her gender-neutral on Jonathan Ross’s TV show, but he’s pretty militant about Mabel’s privacy. He copes better when his little family are indoors; outside the house, things can get tricky, because he has trouble moving from a safe place out into a random world where he is not in command, but also because “I struggle with people touching the kid.” Plus, his celebrity can skew ordinary moments. He writes about being on a boat on a canal with Laura and getting papped and then getting into a row with the photographer – “My unstated plan is to get his camera… I settle for snatching his spectacles to barter for the film”; it doesn’t go well – and tells me of a time when he fell off his bike in Shoreditch and was lying sprawled on the ground, injured, as a selection of hipsters took photographs of him. “The fact that I was a famous person usurped the fact that I was lying on the floor, clearly in pain.” Only a group of older ladies bothered to ask if he was OK.

Sometimes I think Russell Brand is a cautionary tale, almost a mythological figure; a combination of Narcissus, Big Brother, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger – actually, all rock stars at once. But then I remember that, really, he is not like many other people. He’s not ordinary by any stretch: he’s a person for whom fame is like sunlight, who couldn’t have stayed in the shadows without dying. He is built to show off, and that has consequences.

“Yes, but like a lot of people that have access to extrovert behaviour and can seem quite loud and vivid, there’s a fragility also in me. I’ve learned to manage that differently, and I don’t feel so self-damning and self-condemning as I once did, because I’m more aware.” He knows, for instance, that The Trews began promisingly, but descended into political point-scoring, culminating with Ed Miliband visiting his house to be interviewed and Brand deciding that, actually, we should all vote after all, as long as we voted Labour. He admits that the attention the shows generated fed his always-ravenous ego, and he began to use The Trews to feel powerful and get approval. So he stopped. “I still have this tremendous ambitious drive, but now I know, if I give that drive to my ego to contend with, it wreaks havoc.”

He should stay out of conventional politics, I think. “Yes. I’m on the edge of the community – a trickster, a joker, a playful person – I don’t need to be working out how the Metropolitan police force should be run.”

When I remind him how, pre-Miliband chat, he told his many young fans that there was no point in voting in the 2015 election, he is unrepentant, because he felt, back then, that there was no real difference between the main parties. In the 2017 election, however, he endorsed Jeremy Corbyn, because he feels Corbyn is genuinely different from the Tories. But on the whole he doesn’t have much time for politics, because it gets in the way of individual spiritual awakening. He thinks Trump is an idiot, but questions how much he will actually get done during his term in office; he also remembers Obama’s failings in Syria. On his podcast, Brand interviewed Yanis Varoufakis and what he liked most was Varoufakis saying that when people are in powerful roles, their roles form the extent of their power – so that, in the end, they have no true power at all.

Time is up. Shame. I am enjoying our conversation. “So am I,” Brand says. “I’m happy in this conversation. I’m not threatened.” He has to do big talk, he can’t do small: it makes him nervous, and then he might act inappropriately. I say, “Well, you could talk about football, that’s Esperanto for most men.” But he can’t talk casually about football, either, or comedy, because he’s a nerd about both things. He can’t be casual about much, any more, not even sex.

“No. I want to know what is the mystery, what is driving us, where is this all going. The only line you can draw between any of us is between those that think it’s possible for the world to change and those that don’t. Those who think it’s possible for an individual to change and those who don’t. I can’t think, ‘Well, I’ll just wait out my days, I’ll do my cluck, I’ll do my rattle, I’ll do my bird, I’ll wait it out and then put me in the fucking turf.’ I feel it’s possible to change the world.”

Recovery is published on 21 September by Macmillan at £20. To pre-order a copy for £17, go to guardianbookshop.com, or call 0330 333 6846.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion