Robert Carlyle walks into the room holding a small, pale pink alarm clock. Not, it turns out, a way of keeping tabs on how long he has to put up with me, but a present from Lorraine Kelly, whose TV show he’s just come from. “That’s going in my daughter’s bedroom later,” he says, with an hint of paternal triumph.

If being invited on to breakfast TV is any guide, Carlyle is still riding the wave of admiration, respect and popularity he earned in the mid-90s, when first Trainspotting and then The Full Monty propelled him to household-name status. But in truth, he’s been off the film-making grid for a while now, having spent the best part of the past decade in Canada, working in what he calls “American TV-land”. Not seen much of him lately? That means you haven’t been watching Stargate Universe, in which Carlyle played a hunky scientist, or Once Upon a Time, a glossy, meta-fairytale fantasy show with Carlyle camping it up as a human/goblin hybrid called Rumplestiltskin. (In the latter series, which popped on Channel 5 for a year or two, he even had a Ross-and-Rachel-style multi-episode romance with Belle, from Beauty and the Beast, of inordinate interest to the show’s legions of fans. Google “RumBelle”. I dare you.)

It’s safe to say this is not where we might have imagined Carlyle to have fetched up.

Intense, articulate, and roiling with a sense of barely contained aggression, Carlyle’s progress has been almost a cautionary tale for the British film industry. He rode the wave of the UK’s burgeoning cinematic confidence in the 1990s, making it to the big league by the end of the decade: playing a Bond villain in The World Is Not Enough, heading for Hollywood with The Beach, propping up classy art cinema with Angela’s Ashes. The righteous fury he evinced appeared to splinter during the frustrating 2000s, in which his efforts to fight the good fight foundered in a string of underperforming films and stalled production ventures. Now 54, his accent entirely undiluted by seven years in Vancouver, he seems mellow enough, and happy with his lot, even if his centre-parting, floppy-hair gives him a slight but disconcerting resemblance to Lol Creme.

Carlyle is back on the industry treadmill because, of all things, he has directed a film. The Legend of Barney Thomson, based on a series of novels by Doug Lindsay, is his feature-film directing debut (though he did get to direct an episode of Stargate Universe in 2010). It’s very much a love letter to Glasgow, his home city, but it’s far from the Ken Loach-style slice of angry social complaint that we might have expected from him. In fact, Barney Thomson is a comedy, albeit a pitch-black one, with copious gruesome murders and a deranged turn from Emma Thompson, playing Carlyle’s foul-mouthed, chip-guzzling, cigarette-sucking mum.

“I’ve always loved comedy,” says Carlyle. “It’s something I’ve not done an awful lot of, because I keep getting offered psychos. I’m not knocking the psychos – they pay the rent – but the biggest successes I had were comedic, if you think about it. The Full Monty is a comedy, and Trainspotting – well, Trainspotting is not exactly a comedy, but the part is.”

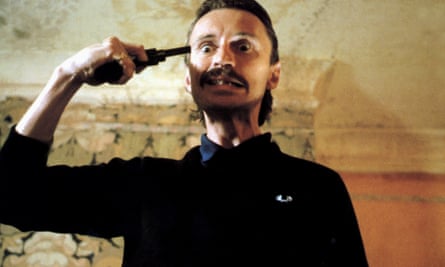

Yes, the psychos. He means the type of damaged, dangerous individual to which his acting persona has been irrevocably, if not entirely justifiably, yoked. Franco Begbie, Trainspotting’s ultraviolent armed robber, may be a monstrous creation, but it gave Carlyle his initial dose of celebrity, which he is still not entirely comfortable with. “It was a false dawn, Cool Britannia or whatever it was. I hate even to say the words. I was fortunate to be in the centre of it, people like the Gallaghers and Damon Albarn were my friends. It was a fantastic time in my life, and I’m glad I went through it. But you wake up and think: what happened? Did it mean anything at all?”

There has always been a gentler side to his acting too – the homeless jobbing builder he played in Riff-Raff, Ken Loach’s film that was his first significant role; the Hamish Macbeth TV show that gave him his first mainstream audience; the ex-steelworker from The Full Monty, and the ex-alcoholic carer in the 2008 film Summer. The latter, directed by Kenny Glenaan and set, like The Full Monty, in Sheffield, marked something of a watershed for Carlyle, when his frustrations with the British film world finally boiled over.

“In the mid-90s, there was a feeling of exuberance, anything was possible. By the time Summer comes along, the country isn’t looking like that any more. I’d seen that budgets had got squeezed and squeezed and squeezed – and on Summer there was no money left in the kitty to publicise the film. Kenny had done a brilliant job on it, and the cast had put heart and soul into it – but nobody’s going to see it. I thought: I’m throwing an awful lot into this, and there’s not an awful lot coming back.” Hence, he says, he came to the decision to actively seek out more lucrative work. “I’d spent my whole career doing small, low-budget films. I thought: I need to make some money here, for the sake of my family.”

His change of tack, he says, wasn’t just about money; doing the bigger films “don’t feed your soul”. The boredom got to him on The World Is Not Enough, for example: he says he spent two and a half days sitting around waiting to do a shot of him just running down a corridor. “Don’t get me wrong, I had a great time doing it, but that ain’t what I become an actor for. Film-making was becoming more and more like that, and I couldn’t stand it.” He also says he appreciates the more intensive acting TV calls for: “you’re on all day, and your arc is just a lot more satisfying.”But his efforts on The Legend of Barney Thomson show that film does have its pulling power, even if he says he had to be backed into a corner to take it on.

It had been floating about as an acting job for years, he says, and there was nothing doing until a Canadian producer friend told him about a “Glasgow script” he should read, and “it was Barney Thomson, again. I thought: this thing’s just never going to go away.” His eureka moment was working out why the script hadn’t worked for him in the past: though the original novels were by a Scot, the adapter, Richard Cowan, was Canadian. (“He is a good guy, but he’s not from where I’m from.”) That was Carlyle’s cue to bring in a Glaswegian writer, Colin McLaren, and after the pair of them had worked on the script, it became a goer. He says he signed up to directing it without realising – “everyone said: this is great, Robert Carlyle directing and acting. I said: ‘What do you mean? I didn’t say that.’ My back was against the wall. Then I thought: nobody knows this as well as me, so maybe it is going to be OK.”

Working on the project has given Carlyle the opportunity to pay cinematic homage to his home turf in the east end of Glasgow; 95% of the locations, he says – such as the Barrowland ballroom, the Shawfield greyhound track and the Bridgeton umbrella – are within a one-mile radius. “It is a love of the city,” he says, “and it’s almost like documenting it for the future, because I think most of these places will be gone in five or 10 years.”

It’s a natural segue to talking about his childhood, when his father used to take him to the cinema four or five times a week, after his mother left them. “My dad used to say: this is to take your mind off what’s missing. I used to sit there looking at my dad and think: it was to take his mind off the whole thing as well.” His dad, he says, loved westerns; Carlyle says that British films of the time – the late 50s and early 60s – became a big favourite. “Hopefully quite a bit of that is in Barney Thomson.”

It seems as if Carlyle is in a mellowing mood generally. The tightly wound, total-immersion actor who once slept on the streets to prepare for a role (Safe), or learned how to drive a bus (Carla’s Song) beginning to recede into the past. “I still take it very seriously,” he says, pointing out he spent a lot of time in a barbers with “a wee guy called Davey” who taught him how to hold scissors and use a razor. He also says the signature moves of his favourite Glaswegian variety acts – Rikki Fulton, Jack Milroy, Jimmy Logan – have found their way into Once Upon a Time’s Rumplestiltskin. “But you’re right,” he says, “I have mellowed a bit. I’d think more than twice about going out on the streets ’gain. But that was my past, that was my grounding. That was me earning my stripes.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion