At the age of 68, choreographer William Forsythe finds himself coming home. After more than 45 years working in Europe, changing the face of dance, he has returned to his native America. “Just in time for the Trump spectacle,” he says, with his low, rolling laugh.

More significantly, since he left his own company in 2015, he has turned his attention back to the ballet studio. After a journey that took him to the outermost shores of contemporary movement, where he has reimagined the classical vocabulary, turning it around, taking it apart and examining it from every angle, he is back working with pointe shoes and traditional forms.

The significance of his double homecoming does not escape him. “I am now a native English speaker living in an English-centric country. In the same way, I feel like a native ballet speaker. It is interesting to look around and see what these very talented people such as Justin Peck, Alexei Ratmansky and Christopher Wheeldon are doing. I think I can contribute to the conversation. And I want to contribute but also to throw down the gauntlet, questioning the choices that contextualise ballet. The music, for example. The visuals.”

At the moment, he is in London, putting his thoughts into practice while creating a new work for English National Ballet, his first for the company, which will have its premiere in a programme called Voices of America, at Sadler’s Wells from Thursday. Called Playlist (Track 1, 2), and choreographed for 12 male dancers, it combines batterie, a virtuosic display of leaping while beating the feet, with music by contemporary artists such as Lion Babe (remixed by Jax Jones) and Peven Everett.

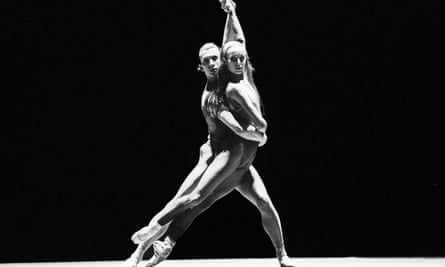

Performed alongside his thrilling 1996 piece Approximate Sonata – which he describes as “an essay on the nature of pas de deux in the mid-20th century” – it asserts his desire to promote ballet as a relevant cultural force and one that should never embarrass its practitioners.

“When we started to work on it, I said to the guys: ‘do you have that nano-second of pause before you say you are a ballet dancer?’ It’s a cultural thing. All these dancers are Olympic-level athletes, true Olympians. Ballet demands reserves of strength and focus that very few people would be willing to muster.

“So we need to own it and demonstrate it. Once you see it supported by this other kind of musical framework, then young people might have fewer reservations about the form, just because it has been placed within a context that is familiar. The music that I have chosen is something they might listen to and it is good. Like Tchaikovsky, in 4/4 time and rigorous.

“You have to remember when the big ballets were being made in the 19th century, they were contemporary art. I think you must speak to the future, to the next generation.”

Forsythe, bearded, slim and full of energy, has the air of a prophet. It’s the first time he has worked with ENB, a company he got to know when they were performing in Paris in 2016 just as he was making Blake Works (to the music of James Blake) for the Paris Opera Ballet. “Even the French étoiles were impressed,” he says with a grin.

“I think Tamara Rojo is doing an amazing job [as artistic director of ENB],” he adds. “I want to work where there is a really good community. There are companies and there are communities. This is a community. It breeds a different approach to work.”

His words land in the wake of reports that the company has been unhappy and unsettled under Rojo’s directorship. “I have seen zero of that,” he says, firmly. “Indeed, I have experienced exactly the opposite feeling. I have the sense that everyone is so relaxed, so willing, able and ready to participate in a creative process.”

He is particularly incensed that Rojo’s relationship with the principal dancer Isaac Hernandez has been held up to scrutiny by the anonymous complainers. Forsythe himself married two of his dancers: Tracy-Kai Maier, who died of cancer, and Dana Caspersen, still his wife and now a world expert on conflict resolution. He knows the territory. “I had the exact same kind of jealousy come up. It’s just the nature of the beast. People don’t have explanations for their own success or lack thereof and so scapegoats are easy to find. It is where people are most vulnerable so why not attack the most vulnerable part?

“I find it unbelievably rude and disrespectful of Isaac. Tamara is a director so she has to deal with that stuff. It’s part of being a director. But to bring Isaac into it and question his skills. He is a world-class dancer, a person who works extraordinarily hard. In my opinion his work is impeccable. What a cheap shot!”

Forsythe’s long experience gives him perspective. He ran his own company – known first as Ballet Frankfurt and then as the Forsythe Company – in Frankfurt from 1984 to 2015. Before that he was a dancer with Stuttgart Ballet, working with choreographers such as Kenneth MacMillan and Glen Tetley. He relished their collaborative approach. “Me being me, I always had suggestions,” he remembers, smiling. “And they were incredibly generous to me. Now I am in the position those artists were in and what I do is consciously and sincerely thank people for helping me out.

“I am working in a way that replicates the best practice I have experienced. One of the big goals I have is to model the best leadership possible. In some senses, I’d like to be the person who I wish my own children would encounter at work.”

Forsythe describes himself as a “complete bunhead”. He has always been obsessed with the history of ballet. “My idea of a good time is to go on YouTube and watch the 23 greatest female variations of all time,” he says with a laugh. Yet he came to ballet relatively late. From childhood he choreographed and performed in high school musicals and became a club dancer. But it was only at the age of 17 that he actually began to study dance.

Once started, there was no stopping him. He performed with the Joffrey Ballet and then at Stuttgart, where he made ballets in the neo-classical vocabulary of his idol George Balanchine. By the time he choreographed In the Middle Somewhat Elevated for Sylvie Guillem and the young stars of Paris Opera Ballet in 1987, it was clear that he was a man who was ready to push ballet into new worlds, making its angles sharper, its balances more precipitous, and its impact more daring.

As he went on, he treated his company as a laboratory of movement, drawing an entire world of thought, philosophy and art into his creations, but moving further and further from what most people recognised as ballet. He says now that this was, to some extent, based on pragmatism. “I didn’t have the money for pointe shoes,” he says. “It was prohibitive. So you adapt. On the one hand the budget we were given was wonderful and you knew what you had but it wasn’t designed to accommodate cost of living increases. So over 10 years our money went down. At the end there was no artistic budget. People said ‘oh you have such a bare aesthetic’.”

His words die away, and he laughs. But although practicalities may have forced his hand, there is a sense in which the radical work he produced in those years has a deep richness of exploration that enables him to look at dance, and ballet in particular, with the clearest of eyes. Now, he is at a point that represents an interesting culmination of all that has gone before. In October, he brings A Quiet Evening of Dance to Sadler’s Wells, a collection of intricate, absorbing pieces, performed a capella. In May, he will be working in New York for the first time in decades, creating a piece for the new arts centre The Shed. He teaches for up to eight weeks a year at the newly opened Glorya Kaufman dance department at the University of Southern California. “It has proved to be very, very nice.”

Returning to his roots is just part of his ongoing journey. “I don’t feel there is any break in the work I have made. But I am back on board with ballet and how I can help valorise this deep, deep knowledge that ballet people have. It’s a big historical thing. I am very interested in what will keep it relevant.”

- English National Ballet: Voices of America is at Sadler’s Wells, London, 12 to 21 April. Box office: 020-7863 8000.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion