It was an idyllic Christopher Street Day in Berlin as we danced, drank, laughed and sang our way to the Brandenburg Gate in celebration of LGBTQ+ pride. A wonderful atmosphere for a city renowned for its social freedoms after two years of pandemic-induced constraint.

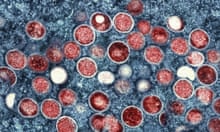

But all over the place were small signs and reminders of monkeypox, the less deadly but still serious cousin of the smallpox virus that’s unexpectedly making its way around the Americas, Europe and Australia, and primarily affecting men who have sex with men.

Those recently recovered had tales to share of confused diagnoses and treatment and a disorganised vaccination program.

Word on the street was that Berlin has very limited supplies of monkeypox vaccine, and that those with active cases and any close contacts were having to spend days on end calling doctors and medical clinics trying to track down a dose, often to no avail.

Those accounts are reflected in guidance from the German authorities noting that the vaccination concept has yet to be worked out and that those who would like one should contact their family doctor or local health department.

Apparently, Berlin is set to receive 80 thousand doses of monkeypox vaccine in late July.

Surveying the crowd, that could well be too little, too late. People had travelled from across Europe and around the world for Christopher Street Day over the weekend. They would be letting their hair down, then heading home. Other countries should be making their own preparations.

As I embraced one friend, I noticed two large scars on his face that he would later explain were the remnants of enormous pustules that had flared up, crusted over, scabbed and finally healed, indicating he was no longer infectious. The scars would likely never dissipate though, hence the effort of a bushy beard to hide them.

Expanding on his experience, he told me of red-raw tonsils and excruciating lymphadenopathy. “I didn’t know we had that many lymph nodes!” he marvelled.

I did. I’m an Australian medical student halfway through my degree, taking a year off to breathe after two years of pandemic study and my own health woes. I push the upper-limits of “mature-aged” at medical school, having come to the vocation late in life after a career in LGBTQ+ health.

Berlin has long been a kind of second home.

As the march progressed, amid the thumping techno and bustling rainbows, I heard more stories. Sores concentrated in the rectum obscuring diagnosis – in the absence of pox on the body, the man’s fever was just attributed to Covid or the flu. The rectal sores must have seemed an unwelcome anomaly though.

This New Yorker article described a similar scenario resulting in screams of pain when going to the bathroom and hours spent delicately trying to keep the area clean.

The mental health impact of forcing people into further isolation was also a topic of conversation, with 21 days generally recommended in the event of a suspected infection. I shudder to think of the impacts of that on the socially and economically vulnerable, especially after the last couple of years.

By the time we reached the Siegessäule – Berlin’s victory column and namesake of a prolific, local queer rag – I had noticed more than a few suspect physical signs. A scar here, a rash there.

“Was that a pock or a pimple?” I wondered as I brushed past a group of scantily clad revellers. I had a feeling masks and sanitiser weren’t going to cut it this time, and I didn’t sense an appetite in this crowd for more lockdowns.

In 2021, as part of my medical studies, I interviewed Australian gay and bisexual men about their experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic. Of the many poignant findings, the one I keep coming back to is the fact that many had experienced a pandemic before, with HIV/Aids devastating this community from the early 1980s.

In the western world, the situation is now more manageable due to breakthroughs in testing and treatment, but HIV/Aids continues to ravage parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

The pain of that first pandemic experience was reflected in my interviews, with participants expressing anger and resentment when comparing the two pandemic responses. These sentiments have also been reflected in research from Austria, Germany, the United States and Canada.

One man in Ontario pointed out: “There’s a Covid-19 panic and crisis so every healthcare system steps in and begins to work. That didn’t happen in the Aids epidemic. We had to fucking fight, and fight, and fight and fight to get the most basic things for people.”

Covid-19 was round two for many gay and bisexual men and men who have sex with men more broadly, not to mention our friends, families and allies.

With the World Health Organisation’s 23 July decision to declare monkeypox a global health emergency, it looks like we might be in for round three. The difference this time is that a viable vaccine to treat monkeypox is already available, along with antiviral medications to limit its severity.

We don’t need to wait for biomedical science to work its magic, and we shouldn’t have to fight and fight and fight – we have the means to address this right now.

Importantly, despite primarily affecting men who have sex with men at present, monkeypox isn’t strictly a sexual transmitted infection.

Rather, it’s borne of close contact and transmitted through respiratory droplets and vesicle fluid encountered on bodies or textiles. Congenital monkeypox transmission from mother to baby in utero is also possible.

It would be a mistake to write this off as a gay disease, in the same way that gay-related immune deficiency syndrome (Grids) and gay cancer served as early iterations of what we now call HIV/Aids. Viruses aren’t like humans, they hold no moral judgement about who’s sleeping with whom. They infect organisms with no regard to sexuality.

One of the hard-won lessons from HIV/Aids was summed up on 23 July by the WHO director general, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, who noted “Stigma and discrimination can be as dangerous as any virus”.

Let’s just get the job done this time, and make sure we don’t scar another generation of marginalised men by turning a blind eye as disease ravages their communities.

Roland Bull is a medical student, writer and stand-up comedian living in Canberra with an interest in sexual health, especially among the LGBTQ+ community